Against Awareness, For Scale: Garbage is Infrastructure, Not Behavior

The Problem with Awareness

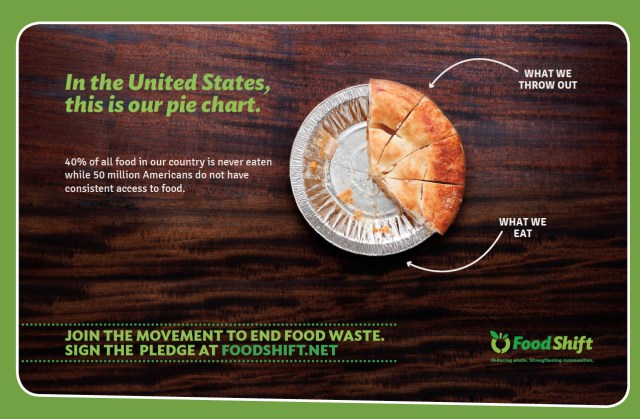

Are you aware that food is wasted in the United States? Are you aware that 40 percent of food is wasted in the United States? Chances are good that you are aware of the first issue: finishing what is on your plate has been a value in North America for generations. Given this long running morality of food waste in general, what does this poster and its statistic–which may well be new to you–do? How do awareness campaigns move towards change?

Despite its ubiquity as a campaign goal, awareness does very little to create change. It is possibly one of the most resource-intensive modes of action with the least payoff. Awareness is usually linked to individual behavior change as its mechanism for change: if the poster above manages to motivate you to go to foodshift.net, you’ll be asked to make a grocery list before you go to the store, become “storage savvy,” and get creative with your leftovers. Sociologists have been studying the relationship of awareness to behavior change for decades, and the results are in: the journey from awareness to behavior change is a long and arduous one, and few make it. Even for those who change their behavior, the scale of the change is often too small to impact the problem at hand.

In the following section, I’ll outline the problem with the awareness theory of social change, then I’ll outline other points of intervention that do the heavy lifting we require.

Sociologists have shown that there are a number of phases between awareness (sometimes called “stimuli”) and behavior change (Gregory and Dileo 2003). First, you make someone aware of an issue: “Hey! Americans throw out 40% of our food!.” Next, the person has to form an attitude (sometimes called an opinion) about that. They have to think wasting food is bad. In short, they have to care about the problem. Third, they have to process the problem, often manifested by learning more about it. They have to do the math. Maybe they click the link in the add and look into how much they waste personally.

For both an attitude and knowledge, or processing, to happen, the person’s values have to align with the awareness campaign. Sometimes that’s a stretch, and sometimes not. But the big kicker is that the person has to be what sociologists called “involved:” they have to already be the sort of person who makes conscious efforts to make change. Whether that means they recycle religiously, go door-to-door asking people to join their religion, or have done a stint in the peace corps, people who change their behaviors are people who already change their behaviors. This finding is actually one of the tenets of effective activism: preach to the converted. If you want to get something done, and you need a bunch of people to do it, go after the people most likely to do it, rather than trying to convert people who don’t agree (attitude) or share values (values).

But let’s say that you’ve capture a whole lot of value-aligned, involved people with your awareness campaigns. Then, there are situational barriers. What if they don’t waste food to begin with? Or they don’t have the resources to use all their leftovers? Or they live in substandard housing where bugs get into their food, forcing them to toss more than they’d like? Some of these are silly, but access, infrastructure and habits are outside forces that can keep the individual willingness to change from turning into behavior change.

Finally, finally, if everything lines up, you still have to turn a one-time behavior change into a habit.

What about skipping all those labor-intensive intermediary steps and shoot for infrastructural change?

The long and the short of it is that awareness–as a way to make social change–has a poor effort-to-result ratio. The premise of awareness campaigns is that individuals are the best unit for change. The individualization of action is a way to fragment it, slow it down, and redirect it to ineffective routes (Szasz 2007, Maniates 2001). Instead, there are different loci for change that scale better, including but not restricted to infrastructure. The advantage to dealing with infrastructure is two fold: first, most environmental and other society-wide problems are not due to individual intent and behavior to begin with, but rather the social, economic, political, and other systems that make some decisions and behaviors more likely or possible than others. Secondly, focusing on these systems for change actually scales up to the scale of the problem. . Changing whether people have access to compost, or, better yet, mandating composting at a municipal level, means that people are much more likely to participate regardless of their values, knowledge, or previous involvement. Better yet, target pre-consumer waste–the infrastructure that really matters–and you’ll have a better site of intervention for reducing food waste (see image below). Even if you get everyone everywhere to eliminate all the food waste that leaves their kitchen, there would still be tonnes of food waste generated.

Pre-consumer food waste consistently outranks consumer waste, regardless of country. Graph from The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

Garbage is infrastructure, not people

Like most genres of waste, food waste mostly happens before it gets to the consumer. Recall that about 98% of all waste produced in the United States is industrial waste. If you want to deal with food waste, deal with pre-consumer waste. Deal with industry, agriculture, and the wider food system. When you look at food waste in its entirely, the tiny drop in a bucket that awareness campaigns can address becomes even smaller. Changing industrial practices and norms (usually via regulation, but also due to other types of pressure) takes a different kind and amount of effort than putting together a poster and website, but is also produces wide scale, long term change.

But you can also impact infrastructure at a more local scale, where your sphere of influence might be stronger, or just more feasible. In my first year at New York University, I wanted to reduce bottled water consumption on campus, and thus decrease plastic waste. My first impulse was to do an awareness campaign about the high quality of tap water in New York City, with the assumption that when people knew tap water was safe and delicious, they would choose tap over bottled water. But then (thankfully) I realized: Being a strict tap water consumer myself, I had no idea why people drank bottled water. So I did some research.

98% of people interviewed at NYU drank tap water some of the time. From the report “H204U: A Qualitative Study of the Culture of Water Consumption at New York University” by Max Liboiron.

Through interviews, observation, and surveys, it turned out that almost all people at the university drank some tap water some of the time. Moreover, the top determining factor that lead to people who drank both tap and bottled water was not water quality, but access to bottled water. Some people did not have a water fountain or sink close to their offices or classrooms (and, it turned out, bathroom sinks do not count–almost no one would get drinking water from a bathroom); others had free bottled water in their office fridges, or via upright water coolers; others took bottled water from home and carried it around with them all day, sometimes refilling the plastic bottle with tap water when they needed it.

The mode of action became clear: change access to bottled water. That is, change the infrastructure. Working with NYU’s Office of Sustainability, we replaced all upright bottled water coolers with in-line water coolers (the same company provided both services, so the switch was fairly painless). We took bottled water off the campus meal plan. We made it more difficult for offices to purchase bottled water. And, we reduced NYU’s plastic bottle foot print exponentially in a year, without a lick of public awareness.

Behaviors aren’t rubbish

All this isn’t to say that using a reusable water bottle or packing up your leftovers isn’t valuable. The decisions you make as an individual–things that stay at an individual scale–are the basis for ethics. Ethics are set of principles of right conduct, a sort of social contract between you and others, and, in the case of the environment, between you and the larger world. They are the foundation for morals, justice, and have the potential to scale into visions of a “good society” that include how individuals and societies should relate to waste and wasting. People with a strong environmental ethic are the “involved” individuals mentioned in the awareness schematic above, and thus are more likely to organize or take part in actions that do scale, from social movements to policy change to infrastructural innovation. So even if individual actions don’t save the world, they are expressions of an ethic that can lead to other actions that do scale.

Problem Definition and Evidence-based Interventions

The bottom line is that without robust and validated definition of a problem, solutions will be shots in the dark. What is the problem with wasting food? We have enough space in our landfills. Leftovers are not a major source of pollution. If the problem is all the extra pesticides, irrigation, and resource input used in Big Agriculture, when half of that food is wasted, and you assume that reducing that waste will also reduce the environmental food print of Big Ag, then you should start with agricultural waste, not post-consumer food waste. If the problem is that shipping municipal waste to landfills is eating a hole in the local budget, and a third of that waste is food waste, then start in homes.

The way a problem is defined forecloses on the types of solutions that make sense. In too many cases, when there is a waste-related issue, solutions that focus on post-consumer waste are immediately proposed before the problem has been properly defined. Such solutions will rarely, if ever, come to bear on the problem. More evidence-based problem definitions will lead to better interventions that can affect the scale, materiality, sources, and systems involved in the problem. There may well be problems out there that are best addressed through public awareness. But food waste isn’t one of them.

Works cited:

Gregory, G. D., & Leo, M. D. (2003). “Repeated behavior and environmental psychology: the role of personal involvement and habit formation in explaining water consumption.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(6), 1261-1296.

Liboiron, Max. (2008). “H204U: A Qualitative Study of the Culture of Water Consumption at New York University.” NYU.

Maniates, M. F. (2001). “Individualization: Plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world?.” Global environmental politics, 1(3), 31-52.

Szasz, A. (2007). Shopping our way to safety: How we changed from protecting the environment to protecting ourselves. U of Minnesota Press.

Max Liboiron is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Northeastern University’s Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute, and has published on the scale of waste, including: “Modern Waste as Strategy,” “Recycling as a Crisis of Meaning,” and “Plasticizers: A Twenty-first Century Miasma.”

2 thoughts on “Against Awareness, For Scale: Garbage is Infrastructure, Not Behavior”

Comments are closed.

Pingback: Page non trouvée | La deuxième vie des objets

Pingback: Against Awareness, For Scale: Garbage is Infrastructure, Not Behavior by Max Liboiron | La deuxième vie des objets